“Austin Askew”–Chapter XXIX– 8/1/66: A Charles Whitman Gazetteer

Tag Archives: UT

Helen Frankenthaler, “Over the Circle,” (1961), The Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, at the University of Texas at Austin.

Joan Mitchell–“Rock Bottom,” (1960-61), The Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin.

James Drake: Anatomy of Drawing and Space (Brain Trash)

This was displayed at the Blanton Museum of Art on the University of Texas at Austin campus from October 19, 2014 to January 4, 2015.

I first saw this during a guided tour, and I think I was the only person in the group who seemed to realize that it was the tennis ball and Kong toy of the artist’s deceased dog. When I saw it the image hit me with such force that I almost began sobbing convulsively.

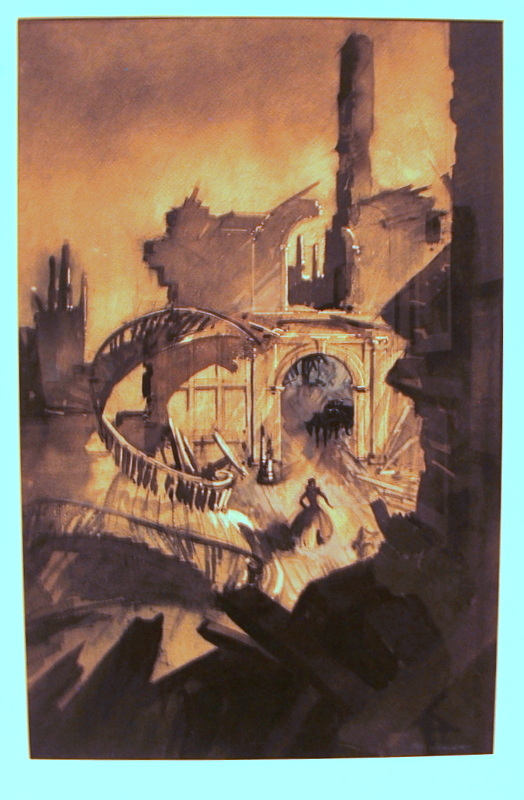

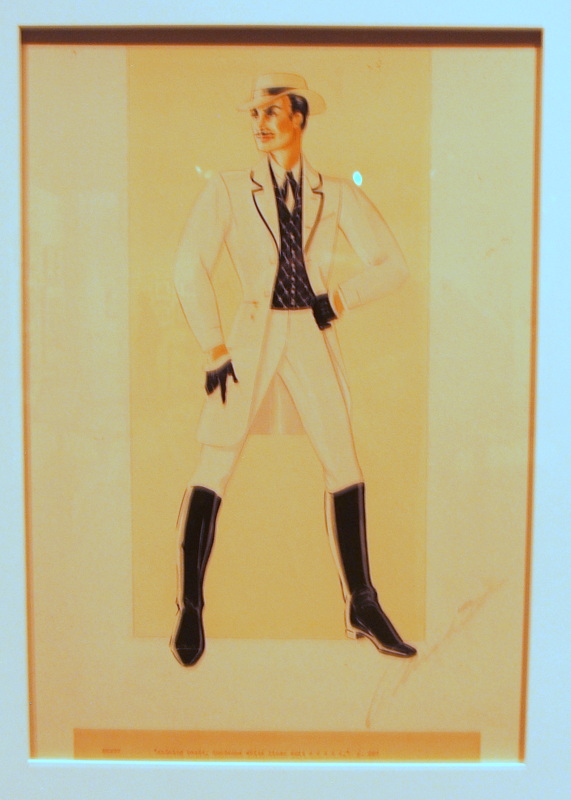

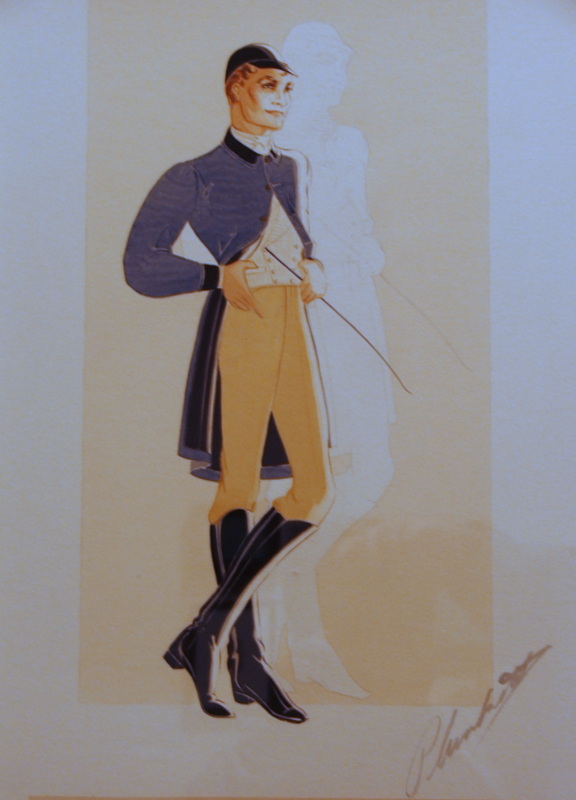

“The Making of ‘Gone With The Wind.'”

Journal Entries. (May 1-7, 2012.)

MAY

Tuesday, May 1st–This day was technically Monday.

Wednesday, May 2nd–I woke around 2am, and got up before 2:30am. Later in the morning I went to the UPS to make some copies and mail off my bills, got food and treats for Belle at Petsmart, and some stuff for me at the dollar store.

I started carrying a wallet for the first time in years. Previously I’d been carrying my bulky checkbook, but I ran out of checks around October and haven’t had the money to re-order them nor much need for them. There seemed to be no point lugging around something so large. I found a brand-new wallet that I’d apparently gotten free with a music magazine some years ago–one of those cheap vinyl wallets with a Velcro strip–but it seemed to do the trick for now at least, so I transferred most of my cards and stuff over to it. Unfortunately. it bulges like George Costanza’s wallet.

I read, then retired a little after 5pm.

Thursday, May 3rd–I woke a little after 4am, and decided to make today my art day. I hadn’t been to the Blanton in over a year, and I wanted to catch their Hudson Valley School exhibition before it leaves next week. So I took care of Belle and got ready.

After I left the house I went into a panic, afraid I’d left a stove coil on or that today would be the day the workmen invaded my home to replace my privacy-affording wooden balcony wall with one of those wide-open, goddamnable metal railings.

But I forced myself onwards.

Directly in front of me on the bus was a man who stank as if he’d shat in his pants and sat in it afterwards–rather like a baby or an old man. Either he was retarded or his barber was–he had the Moe Howard/Incan laborer bowl cut.

I got down to campus, went to the bank, deposited some money and got a little cash, then strolled slowly across campus. I got some pictures of the Littlefield House, stopped to piss in the new, hideously ugly Experimental Science Building, photographed the mustang statue in front of the Texas Memorial Museum, then went to the Art Building to cool my heels until the Visual Arts Center opened.

I’d tried to go to the VAC last year, but it was closed the day I went by. It occupies what used to be the old Archer Huntington Museum space, but now hosts student art exhibits.

The VAC didn’t open on time, so I wandered the Art Building, wishing I was in art school rather than marching towards a boring career or abject poverty, the way I am now.

Eventually, a little girl with a haircut fifteen years out of style came by, ten minutes after the hour, and opened up.

The VAC consists of two floors of galleries, but the upper level was closed, so I made short work of the three lower-level galleries. I generally thought the work much better than what I’d seen at that art space at M___’s birthday party. I even took note of a few of the artists’ names, for future reference.

I briefly spoke to the girl behind the information desk. She called me “Sir,” which made me feel like an old fart.

Outside, I started to look for a food kiosk, but those I saw either weren’t open yet or didn’t have anything I wanted to eat.

I went for the first time into the Alumni Building, which was nice, if a bit overdone. I asked a gal at the information desk to look up a friend who was a UT graduate. She didn’t have the clearance to give me his contact information, but she sent him an e-mail, mentioning me, so I’ll see if he gets back with me. He was a friend from when I attended Austin Community College (1993-1994), and I’ve not seen him since about 1996.

I then went over to Jester Center and had a salad for lunch in the cafeteria.

From there I went over to the Blanton, toured the amazing Hudson River School exhibition, then went upstairs, looked at the “Go West” exhibition, and the Modern, Contemporary, and European collections.

I spoke to one guard about the photography restrictions for the “Go West” exhibitions, and he reminded me not to use a flash. I furrowed my brow, and said I never use my flash anyway, as it makes everything look like an eight-year-old’s birthday party. He found this amusing, and said, “You’d be surprised how many people don’t realize that.”

One guard, a rather dumpy-looking woman who was not managing the transition from her twenties into her thirties very well, took umbrage to my camera beeping. (“Your camera’s audibles,” as she called it.) I explained that I hadn’t a clue how to shut that off. After that I got paranoid. She seemed to make her rounds through the main gallery with much greater frequency, as if she suspected I was about to do something bad, and I made a point of waiting until she was well out of earshot before I snapped my pictures.

In one of those delightful moments when the I-Pod and real life intersect, I walked into the gallery that houses Cildo Meireles’s “Missao/ Missoes [How to Build Cathedrals],” which is made of 600,000 coins, 800 communion wafers, 2000 cattle bones, 80 paving stones, and black cloth, just as Ennio Morricone’s “Ecstasy of Gold” came on.

I saw a stunning video portrait of HSH Princess Caroline of Monaco by Robert Wilson. In the learning center/library, I made my own artistic arrangement of colored building blocks. In the next room I came across an old woman in a wheelchair, and commented to her, in awed tones, that the wagon train painting we were both looking at had been in one of my books when I was a child.

All during my visit I tried to take interesting close-ups of some of the paintings, as full-length photos of them usually turn out badly with me. I don’t know as I did well even with this.

I was in the Blanton a little over two hours. By the time I got outside again it was already as hot as a pawn shop pistol outside. I went to the PCL, looked up a biography of Denton Welch, then headed back outside. I thought I was going to have a heart attack trying to walk uphill in that heat.

I went to the Architecture Library, found some stuff I wanted to photo-copy, but realized I’d need a good deal of money to copy it all, so I decided to hold off making the copies until a later date. I left, quickly caught a bus, and was back home a little after 3pm.

Belle was thrilled to see me, and had left a ponderous amount of piss and shit on and off the newspapers for me to clean up. The apartment had, thankfully, not burned down, nor had workmen come into my apartment to start fucking with the balcony.

I walked Belle, showered, and puttered around online. I was sore as hell from all the walking, and knew I’d feel even worse the next day. I retired, I think, a little after 8pm.

Friday, May 4th–I had another dream were I was going back to college. I had moved into a tiny studio apartment with some other guy. Who was he? Why would I willingly agree to share an apartment with anybody?

Anyway, it was night-time and this guy fell asleep on his bed. I fell asleep in an armchair, watching what seemed to be a marathon of David Janssen’s old TV show, “Harry O.” When I woke up, there was Janssen, in a tan wind-breaker, scowling, while piloting a small boat. (This is interesting, because now when I look up Janssen on IMDB, there’s a quote by him that says, “TV is my sleeping pill.”)

Publicity photo of David Janssen, circa 1974.

I looked around and decided to fix up the apartment. I found the more I cleaned and re-arranged, the larger the apartment got. The room was actually growing. But would I be able to keep the apartment? I hadn’t actually bothered to register for classes and it was too far along in the semester already to do so.

I noticed that there were two small shelves on the wall near my bed, but you could hardly put anything on them because there were large plants on them already, with long, spreading, brown branches that crowded everything else. I think my mom had put them there when I moved in.

Upon closer examination I found these plants to be aromatic, but also apparently dry and possibly even dead. I took them down out of the shelves and the room got even larger.

Before long people started arriving to visit us. Our room was the hip place to be. My bed was turned into a rather ugly, poorly decorated Turkish corner with red-and-white pillows and upholstered frames. Indeed, it looked as if a couple of divans had been turned upside down to achieve this effect.

I was getting ready to take my seat and start holding forth to my fans, when I was approached by a young man I know from online. He seemed nervous, and desperate to talk. My personality was transitioning from its normal manner into the larger-than-life stage manner I used when entertaining. It was as if this metamorphosis was happening independent of my will, and that it was important for me to start entertaining soon. The music that accompanied my “show” was starting up. The crowd was getting restless. but my young friend seemed very anxious, so I took a seat at a table and let him talk.

He was upset and getting more so. He seemed almost on the verge of tears. He was so unhappy about his life. He fidgeted a great deal–especially with his hands. I noticed his fingers were dusted with potting soil, and so I concluded he’d recently been working out in a garden. He was just beginning to get to his point when I woke up.

I woke around 8 or 9 in the morning, sore, but about as rested as I ever get. I spent much of the day puttering around with my Word Press blog.

Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys has died. I admit, I never figured out how to pronounce his last name. I assume it sounded something like a cat vomiting.

Saturday, May 5th–I woke around mid-morning. Though there were construction crews around today, they made no noise.

I did a tutorial on Mac OS X Lion, then read a little. There was a good-sized storm at night.

Sunday, May 6th–I had a dream about my apartment complex. For weeks now construction and grounds crews have been making a terrible racket, fucking shit up, cutting trees and brush, killing other trees with their clumsiness, leaving trash and half-eaten bits of food all over the grass, tearing off rotting pieces of the flimsy materials from which these shitty apartments were made and nailing up new replacement pieces, and for all this bullshit I am to be rewarded with a grossly inflated rent in a few month’s time.

I have been worried that these mouth-breathing assholes would clear out the wilderness area in the middle of the complex, a steep ravine with a small creek at the bottom, where deer and other creatures live.

In this dream I was looking out the window and saw a lot of grounds work going on. Office personnel were even mowing the grass–something that never happens. And there were more office workers than are normal. I stood back a little from the window, so I’d not be seen, and so the office people wouldn’t feel they could come up and make a request or order to me.

But then I looked to my right and saw a small tree being cut down. Naturally, this upset me. But when the tree finally fell its background changed dramatically. And everybody in the complex, indoors and out, noticed the change.

It turns out that the crew of dumb asses had actually made something fairly attractive. While they had cleared out much of the undergrowth for the wilderness area, they’d turned the space into a lovely park and an 18th-century French garden! While this might not be the optimal home for the wildlife, there was still plenty of green cover.

Palace of Chantilly with the gardens of André Le Nôtre — 17th century.

And so I strolled down to see this new work, and of course got to show off and point out to my uneducated neighbors the various features of the design, including the grand allées and vistas that terminated in the formal entrance portals of the Neoclassical buildings in the distance. (As if there’s be Neoclassical buildings anywhere around here! My apartment complex is built in Late 70s/Early 80s Butt Ugly, complete with those pointless zig-zag shed roofs that were so popular back then.)

Monday, May 7th–I had to call today to check to see that my Food Stamps benefits had been deposited. After that, I went to Randall’s, where I bought a salad, chips, and a drink, and ate them in their dining area, watching the activity in the early voting area a few feet away.

(When all the poll workers at your neighborhood early voting location look like Michel Foucault, you know some serious shit’s about to go down.)

I then went over to HEB for my main bout of grocery shopping. My cashier initially mistook me for a woman. (I guess the 1970s porn star moustache threw her.) Now there is nothing at all feminine about me, but a thyroid problem and a fondness for food have unfortunately left me with soft, pillowy breasts, and the general figure of a post-menopausal woman of around 60 years of age, who squeezed out five children and now manages a laudromat somewhere in the Deep South.

I had a good deal of groceries to carry home, and was worried I’d not get back before the promised rain arrived, but though my load was heavy, it wasn’t as bad as it’s been in the past, and I didn’t hurt myself lugging it. The storm didn’t come until quite awhile afterwards, but it was considerable.

Later on I puttered, did some blog posting, and read in Huxley.

Stairs of the Battle Hall Architecture Library, University of Texas at Austin.

Image

(Photo by JSB.)

“Austin Askew”–Chapter VIII–Major George Washington Littlefield

Ego, or at least a healthy self-regard, is the first building block used by the self-made man. After all, a man must have some sense of his own worth before he can decide he ought to improve his own lot, for otherwise he will just remain in the circumstances into which life has placed him.

Once a man becomes successful, however, he usually enjoys commemorating his achievements. He wants to be remembered. If he has no sons to carry on his name, he at least wants to see that name carved somewhere in stone and bronze, on a building or monument.

I say this going in that I am not in the least disparaging the ideals of charity and philanthropy. Those are noble qualities indeed. I merely suggest a desire for immortality often accompanies motives that are otherwise selfless and public-spirited.

Go all over Texas and you can quickly suss out the big shots of past and present by the repeated appearance of certain names on buildings, streets, monuments, and institutions. In Galveston, for instance, it’s hard to avoid the name Moody, while in the Metroplex evidence of the Bass family is everywhere. Every other building at the University of Houston seems to bear the name of Cullen, after the oil-rich family that gave many millions to that school.

In Austin you find the name Littlefield everywhere. It adorns a major office building, a shopping/apartment complex, a UT dorm, a huge UT fountain, and a large Victorian house, and I’m sure I’m leaving some things out. But the newcomer and probably many longtime residents might be somewhat in the dark as to why that name is so important.

Major George Washington Littlefield was the Donald Trump of his day, albeit without the ridiculous hair. He was a banker, businessman, cattle baron, philanthropist, and unrepentant, unreconstructed Confederate. Just about every enterprise he put his hands to flourished.

Littlefield was born in Panola County, Mississippi in 1842, the eldest of four children. He and his family moved to Gonzales, Texas in 1850, and his father died three years later. Littlefield’s skimpy education was gained from a tutor at home and two years at Baylor College in Independence, but he learned practical business principles from his mother, and by the age of 16 he was helping her manage the family plantation and 200 slaves.

In 1861 when he was 18, Littlefield signed up with the Eighth Texas Cavalry, which was best known as “Terry’s Texas Rangers.” He saw action at the battles of Shiloh, Murfreesboro, Bowling Green, Lookout Mountain, and Chickamauga, among others, and was made a Captain before his 19th birthday. In 1863 he was sent home on furlough to do some recruiting, and while there he married Alice Payne Tiller, before returning to the field.

In December of 1863 at Mossy Creek, Tennessee, a Union shell exploded near Littlefield. Some of the shrapnel detonated cartridges in his ammo belt, tearing an eleven by nine-inch chunk out of his hip, all the way to the bone. Littlefield was carried to a surgical tent, where he was given a bottle of brandy.

The doctor told Brigadier General Thomas Harrison that there was no point in wasting morphine on Littlefield, because he’d clearly not live through the night. Hearing this, Littlefield somehow managed to sit up and make a toast: “Gentlemen, I drink to your health through tomorrow–when I am confident I shall still be here. I will drink to the Division Surgeon, who predicts my death at morning.” Harrison promoted Littlefield to the rank of Major for his bravery.

But the war was effectively over for Littlefield. He was tended by his body servant, Nathan Stokes, and spent many months hospitalized. He resigned from the Confederate Army in June 1864, and amazingly, by the end of 1867 was able to walk without the use of crutches.

Things went reasonably well at the Littlefield plantation between 1864 and 1868, but worms, drought, and two floods ruined the cotton and corn crops from 1868 to 1870.

Now between 1861 and 1865 most of the able-bodied young men from Texas were off fighting the Civil War, which meant that there weren’t a lot of people around to tend to the cattle. Consequently, cows ran wild everywhere and bred to an excessive degree. By the end of the war Texas was overrun with cattle.

Soon enterprising Texans like Littlefield realized that there was a market for beef up north, and started rounding cows up and driving them up the Chisholm Trail to Kansas. Littlefield made so much money off the cattle business that he had to bring in brothers and nephews to help him in his operations.

During one drive Littlefield’s cowboys went on ahead of him with the herd into a Kansas rail junction town. Littlefield arrived some time later to find his cattle wandering loose in the streets and all his cowboys in jail. It turns out a few of his men had ridden into a saloon on horseback and ordered drinks, and the sheriff arrested the whole crew.

He started the LIT ranch in Oldham County in 1871, but sold it four years later. He owned ranches in Mason, Menard, and Kimble Counties in Texas, and the LFD ranch in New Mexico. (The initials “LFD” stood for “Left For Dead,” and were a reference to Littlefield’s Civil War experiences.)

In 1901 he purchased the 240,000 acre Yellow House Division of the three million acre XIT ranch. In 1913 the town of Littlefield was founded on a portion of the Yellow House ranch he had set aside for settlement. About the only event of note that ever happened in Littlefield was the birth, in 1937, of Waylon Jennings.

George and Alice Littlefield had only two children, both of whom died in infancy, but between them they had twelve nephews and seventeen nieces. Littlefield paid for the education of all twenty-nine, and gave each niece a home when she married and set each nephew up in his own business.

In 1883 Littlefield moved to Austin, where he took a position as board member of Eugene and Pierre Bremond’s State National Bank, before starting his own, American National Bank, in 1890. (The Littlefield Mall, a retail and apartment mixed-use structure, stands on the site of the old John Bremond and Company building, and its parking garage services both the Littlefield and Scarborough Buildings at Sixth and Congress.)

Littlefield owned the Driskill Hotel from 1890 to 1903 and ran his bank out of the building. (You can still see the antique vault in the hotel’s lobby.)

In 1910 Littlefield started construction on the office building that still bears his name, an eight-story Beaux Arts structure at Sixth and Congress designed by local architect C. H. Page. Opened in 1912, the building originally featured a roof garden with a pergola, which soon became a popular place for Austinites to dine. But Littlefield was annoyed that the Scarborough Building across the street was taller, so he scrapped the roof garden and added a ninth story, as well as an annex featuring Turkish and Russian baths. For a little while the Littlefield Building was the tallest building between New Orleans and San Francisco.

The structure was shaped like an “E” so that all the offices could get light and air. It featured refrigerated spring water, electric elevators, a central vacuuming system, marble-lined restrooms, and all the state-of-the-art conveniences of the day.

The most important tenant was, of course, the American National Bank (now Bank One, Austin), which was entered through a pair of huge, 2 ½ ton, 10′ 4″ by 6′ 9″ bronze doors on the corner of 6th and Congress. The doors were sculpted in Austin and cast by Tiffany and Company in New York City, and featured scenes of ranch life on its panels and Longhorn skulls as door handles. Murals depicting more western landscapes dominated the bank’s lobby.

The bronze doors now sit a few blocks away from their original home, in UT’s bland Ashbel Smith Hall. The bank lobby is now the site of a sandwich shop.

In 1908 Colonel William Frederick Cody, aka “Buffalo Bill,” wrote his Austinite friend Major Joe Booth, complaining that some guy named McDonald had dismissed his Wild West Show as a “circus.” Cody regarded the show as an “educational entertainment of our own western life.”

Seeking vindication and recommendations, he asked Booth, “Will you please ask Major Littlefield if he will give his opinion, as to whether it is a circus or not? I believe the Major will do it for me….Major Littlefield’s opinion would carry a lot of weight, for he saw my Wild West when it was in its infancy, and knew me before I started it, and knew I was a Scout and Pioneer, and never was a circus man, as you know.”

Littlefield served as a member of UT’s Board of Regents from 1911 until his death, and indeed, most of his charitable donations were to the school. Thanks to the Reconstruction government that ruled Texas immediately after the Civil War, there was a law on the books that stated that Texas history and civics textbooks had to reflect a pro-Northern, anti-states rights viewpoint, and this rankled Littlefield and other Confederate veterans.

Littlefield wanted an unbiased history of the South to be written. UT history professor Eugene C. Barker explained to him that most Southern historical materials then resided in Northern libraries, and for a work of the sort Littlefield had in mind to be written these materials had to be purchased and utilized. In order to achieve these ends the Major established the Littlefield Fund for Southern History, with an endowment of a quarter of a million dollars.

Apparently, there was talk for a time of moving the UT campus to property the school owned along Town Lake. For whatever reason Littlefield didn’t want this to happen, and gave the school $500,000 toward the construction of the Main Building on the proviso that the university not move.

In 1918 Littlefield, at the suggestion of Professor Reginald Griffith, purchased the library of Chicago book collector John Henry Wrenn for the University at a cost of $225,000. The Wrenn collection consisted of almost 6,000 rare seventeenth and eighteenth century English and American books, as well as manuscripts and page proofs, and was considered quite a prize.

Wrenn had purchased many of his books from Thomas J. Wise, a respected British bibliographer, collector, and dealer. In 1934, however, two young bibliographers published a book, “An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets,” which, despite its seemingly esoteric nature, exposed Wise as a master forger. UT’s Wrenn Library has almost one hundred examples of Wise’s work, although I can’t help but think Major Littlefield would not have been happy that he didn’t entirely get what he paid for.

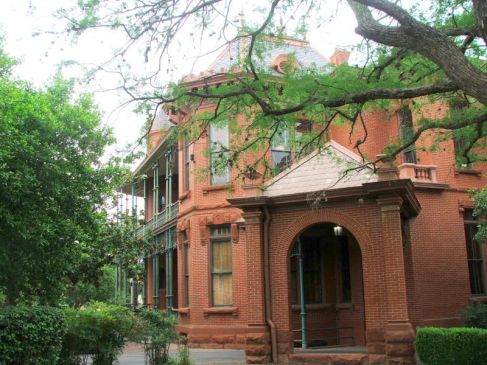

Major Littlefield died in 1920 at the age of 78. His body lay in state in the corridor of UT’s Library (now known as Battle Hall, which was designed by Cass Gilbert, architect of the Woolworth and US Supreme Court Buildings, and which is currently UT’s Architecture Library). His funeral service was conducted at his home. UT was closed the day of the funeral, and many Austin businesses closed for the service.

Littlefield was buried at the north end of Oakwood Cemetery. (If you’re driving on East MLK by Disch-Falk Field you can’t miss it–the Littlefield monument looks like an enormous granite deep freeze.)

The Littlefield monument is carved out of grey granite from Vermont and cost $40,000. It weighs 100,000 pounds, has a base 18 feet long and 9 feet wide, and is 15 feet tall. Four teams of horses and an eight-wheeled wagon were used to haul the stones from the rail yard to the cemetery, and it was said that the delivery was “the heaviest piece of drayage work ever undertaken” in Austin up to that time.

When Littlefield’s will was probated it was front page news. He left the bulk of his estate, estimated to be in the neighborhood of $8 million to $10 million, to his widow, and when she died in 1935 what was left over from her share went to a variety of relatives and friends. UT was the estate’s second largest beneficiary.

His former slave and lifelong servant Nathan Littlefield Stokes received a cottage and weekly pocket money for the rest of his life, and when he died in 1936 at the age of 105 he was buried in the Littlefield plot, which is rather surprising considering that in those days racial segregation was in force even after death–black and white did not normally mingle even when six feet under.

Over the years a legend has developed that Major Littlefield’s donations and bequests to UT were contingent on every building on campus having its main entrance facing south, but a quick tour of the campus shows that this is not true and that there were buildings built in the Major’s time and in the decades immediately afterward that don’t face south. Some don’t even have minor doorways on their southern facades.

The house Major Littlefield built is one of the finest Victorian mansions left in Austin that the general public can view. It’s located on 24th Street and Whitis on the UT campus, just behind the University Methodist Church. The second floor has been taken over by drab private offices and is off limits, but most of the first floor has been beautifully restored and can be examined during normal business hours.

The house was built for $50,000 between 1893 and 1894 by James W. Wahrenberger in the French Gothic Revival style popularized by Eugene Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, and consists of two main floors, an attic, and a basement, built of red brick with sandstone highlights, blue granite columns and front steps, slate roofing, and with elaborate wrought iron work on the porches.

Alice Littlefield left the house to UT when she died in 1935. Prior to her death she had apparently commented that she hoped the house could be used as the official residence for UT’s President, but the idea was never formalized in writing and so nothing came of it.

Over the years UT has used the house and adjoining carriage house for a variety of functions–if the floor plans I have before me are correct, the basement is still honeycombed with tiny rehearsal rooms from the days the Music Department used the building. The Navy ROTC converted the attic into a firing range.

Legend has it that Alice Littlefield was a frightened, depressive woman, and that when he went on business trips the Major would lock her up in the attic to protect her from marauding Yankee rapists. Apparently on one such occasion she was attacked in the attic not by humans, but by bats, and it is said her ghost haunts the house to this day, impatiently waiting for the Major to come home.

Granite steps lead up to the elaborate front entrance of the house. A porch with wrought iron columns and railings wraps around the southern and eastern sides of the house, and there’s a service porch on the northwest side and a porte-cochere on the northeast.

The front door opens into a vestibule that gives access to the library at right and front and back parlors at left. Straight ahead is the main hall, which is dominated by a fireplace and, behind a pair of arches, the main staircase.

Behind the library is a cross hall, then the long dining room, which ends in a bay window and has access to the butler’s pantry. There is a wing on the northwest end of the house that once contained the kitchen, and rooms for servants and storage.

The second floor plan is basically the same as that of the first. The circular turret on the southeast corner of the house rises three stories, while a rectangular turret extends four stories over the entrance vestibule.

Several basic principles went into the design of large houses in Europe and America in the Victorian era. First, a room was usually designed for one separate function, unlike today, when we often eat, watch TV, get on the computer, do homework, play games, and so forth, in just one room. In the more elaborate Victorian households there were often rooms for polishing silver, for arranging flowers, for brushing hats and clothes.

Second, some rooms in the large Victorian house were designed to be used mostly by women, and others by men. Each sex usually got its own suite or cluster of rooms, and the sexes were kept segregated. We can see this even in the Littlefield house.

Men and women took dinner together in the dark, masculine dining room, but afterward, the women would go across the hall to the front and back parlors, where were decorated in a very feminine style, with gold and cream tones. And usually, the women went to bed earlier than the men. Meanwhile, the men would either stay in the dining room, or go into the library or even out onto the porch, for drinks and cigars.

And though the Littlefield house is large by all modern standards, you have to remember that the house was usually full of nephews and nieces, as well as other guests, so its ample facilities were probably strained.

Littlefield left UT $300,000 for the construction of a girl’s dormitory to be named after his wife. The four-story Spanish/Italianate structure was built a block northeast of the Littlefield house. A few years ago there was a great hue and cry when UT made the drastic decision of turning this all-girl sanctuary co-ed, albeit just for the summer. Before the boys were allowed in, though, dormitory officials put such treasures as Alice Littlefield’s china, which had been on display in glass cases, into locked storage.

Major Littlefield also left UT $250,000 for the construction of a memorial arch that would serve as a principal (southern) entrance to the campus and that would be designed to honor the Confederacy. From the first, this project has been controversial, and it remains so today.

Not long after Littlefield’s death the idea of the arch was given up and replaced by a scheme to build a huge terraced fountain adorned with statues of Southern heroes, sculpted by Pompeo Coppini. Later still the design was simplified somewhat and most of the statues were erected along the edges of the South Mall, south of UT’s Main Building and north of the Littlefield Fountain.

Coppini is probably best known for the cenotaph he designed in front of the Alamo. It’s a huge, white monument that features a winged naked man rising, phoenix-like, the way so many winged naked men do, victoriously from the ashes of defeat.

Statues of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Albert Sidney Johnston were placed on the west side of the Mall, statues of Texas politicians John H. Reagan and James S. Hogg went up on the east, and statues of Jefferson Davis and Woodrow Wilson were set up on the north end. Some years later a statue of George Washington was erected on the north end as well. (Dirty-minded students say the Washington statue looks obscene from one angle.)

In later decades many students protested the presence of these statues, saying that they were symbols of a racist past. As a result, the statues of Jefferson Davis and Woodrow Wilson were taken down in 2015, while the Lee, Johnston, Reagan, and Hogg statues were removed in 2017.

The Fountain itself was designed by Coppini and arranged by Paul Philippe Cret, the architect of UT’s campus master plan, the Main Building, and many other structures at UT. The granite and bronze Fountain, which was turned on in 1933, features a pool 150 feet in diameter, and pumps 3,000 gallons of water a minute through an underwater motor. The Fountain was dedicated to the memory of the 96 men and women from UT who died in World War I, and is said to represent the reunion of the North and South as one American nation, brought together to fight a common enemy in World War I, after having been torn asunder by the Civil War.

At the back of the Fountain is the figure of Columbia (basically the Statue of Liberty’s older sister) riding on the Ship of State and carrying the torches of liberty and fruitful labor, guarded by a semi-nude soldier and sailor. (There’s a good shore leave joke in here somewhere.)

In 1950 some frat boys who were clearly desperately in need of the company of women took Columbia’s measurements. She was found to be 105 inches tall, with a 96-inch bust, 84-inch waist, and 101-inch hips. (Baby got back!)

Columbia’s ship is pulled by three seahorses who have water shooting out of their nostrils. Two of the seahorses are being ridden by tritons, demi-gods from the sea, who are of course naked and seem to be wearing World War I aviator headgear with horns sprouting out of them. The tritons are also trying to subdue the riderless seahorse in the middle, but seem to be only semi-successful, and their faces are contorted in agony, no doubt from trying to ride horses naked .

Coppini rather floridly explained that the riderless seahorse was meant to represent the wildness of mob rule, while the ones subdued by the naked men on their backs were supposed to represent the usefulness of manpower. I don’t know about any of that, but I have heard the campus legend that if ever a virgin graduates from UT the seahorses will pull themselves up out of the granite and bronze and fly away.

Texas folklorist and UT professor J. Frank Doble hated most of the changes made to the campus during his time there. He thought the UT Tower was a monstrosity that would’ve looked better on its side. And he really hated the Littlefield Fountain. When World War II broke out he said, “Scrap metal is badly needed. This is a good time to get rid of those idiotic riders and amorphous horses.”

UT students, on the other hand, have gotten much use out of the Fountain. Fraternity pledges, freshmen, and Aggies have been dunked there. Prospective bridegrooms have been dipped in the waters in order to cure them of their sexual impurities prior to their weddings. The pool has been home to ducks, giant lily pads, a 75-pound alligator named “Charley,” and untold gallons of frothy soap bubbles. And if a grab-bag like that won’t ensure the immortality of the Littlefield name, then I don’t know what will.

(Correction and Addendum:

In the April 28th issue of the “Downtown Planet,” I wrote an article, separate from my column on the Bremonds, describing an historic plaque that was to be unveiled at the former site of John Bremond and Company. Among those invited to the ceremony were Bremond family members and descendants of the original members of Hook and Ladder #1, the fire company John Bremond organized.

Apparently the connection between the Bremonds and fire fighters ran deep, and for several generations. I mentioned in my column that John Bremond, Sr. and several of his descendants were fire fighters. I received an interesting phone message from Mrs. Walter Bremond III that I thought shed additional light on this subject, but unfortunately we had already gone to press by that time.

Mrs. Bremond said, “My husband, when we first married, he said, ‘Bobie, if you get into trouble while you’re on the road or in another town, always go to the fire department. Don’t go anywhere else–go to the fire department.’ And I thought that was kinda funny, but I promised I would do it.

“I’ve never had any–knock on wood–any problems, but if I had I would have looked up the nearest fire department, like he said. So they all believed in the fire department, the personnel there, and I thought that was the best recommendation for that bunch that I have ever heard and I would like for them to know that as a bride those were my instructions.”)

—May 12, 2005

(Post-post-script:

The removal of the Confederate statues from U.T.’s South Mall leaves several plinths that need filling, and I suggest that the University of Texas do with them what the British do with the “Fourth Plinth” in Trafalgar Square in London.

{This is a plinth that, for one reason of another, has never been formally assigned a statue, and so has in recent years temporarily showcased contemporary works of art.}

U.T.’s empty stone plinths are set in beautifully landscaped parts of the campus, and therefore would be ideal sites for UT art students and art faculty to display their own sculpted works.)

–May 28, 2015/August 21, 2017